03.07.2023 - 01.01.2100

03.07.2023 - 01.01.2100

In the second half of the 1700s Spain broke away from its foreign dependence in the field of printmaking. The training of qualified draughtsmen and printmakers, notably Manuel Salvador Carmona, made it possible to record in prints the major cultural and scientific undertakings promoted by Enlightenment thinkers. The culmination of this process was the publication of Francisco de Goya’s Caprichos in 1799. Although the prints of this period are well known, the preliminary drawings on which they were based are not. Their utilitarian nature has led them to be considered of secondary importance in art history. Yet the quality of a print hinges on the properties of the preliminary drawing; it is impossible to produce a good print without a good drawing. From Pencil to Burin – two of the instruments most widely used by draughtsmen and printmakers – shows the different uses to which drawings were put during the creation of a print, with examples ranging from those made by the artists who designed the images to those produced by the printmakers in their workshops. The variety of techniques employed and their adaption to the subject matter offer viewers a survey of Spanish drawings in Goya’s day.

Area 1

Manuel Salvador Carmona was the foremost engraver in 18th-century Spain. The master of a generation of artists at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, he always attached importance to the practice of drawing, which he considered essential for a good printmaker. His portraits and self-portraits illustrate this idea and reflect his career and personal life. His first self-portrait bears witness to the years he spent in Paris on a scholarship, constantly ‘with a burin or pencil in his hand’. Later on he portrayed himself drawing, underlining its importance as a principle of artistic practice. An indefatigable draughtsman, he portrayed his entire family using the French ‘trois crayons’ technique – a combination of black, red and white chalk. The portrait of his wife, Ana Maria Mengs, may have served as a model to be included in a print also featuring his own self-portrait. The image was never engraved and only the preparatory drawings are known.

Area 2

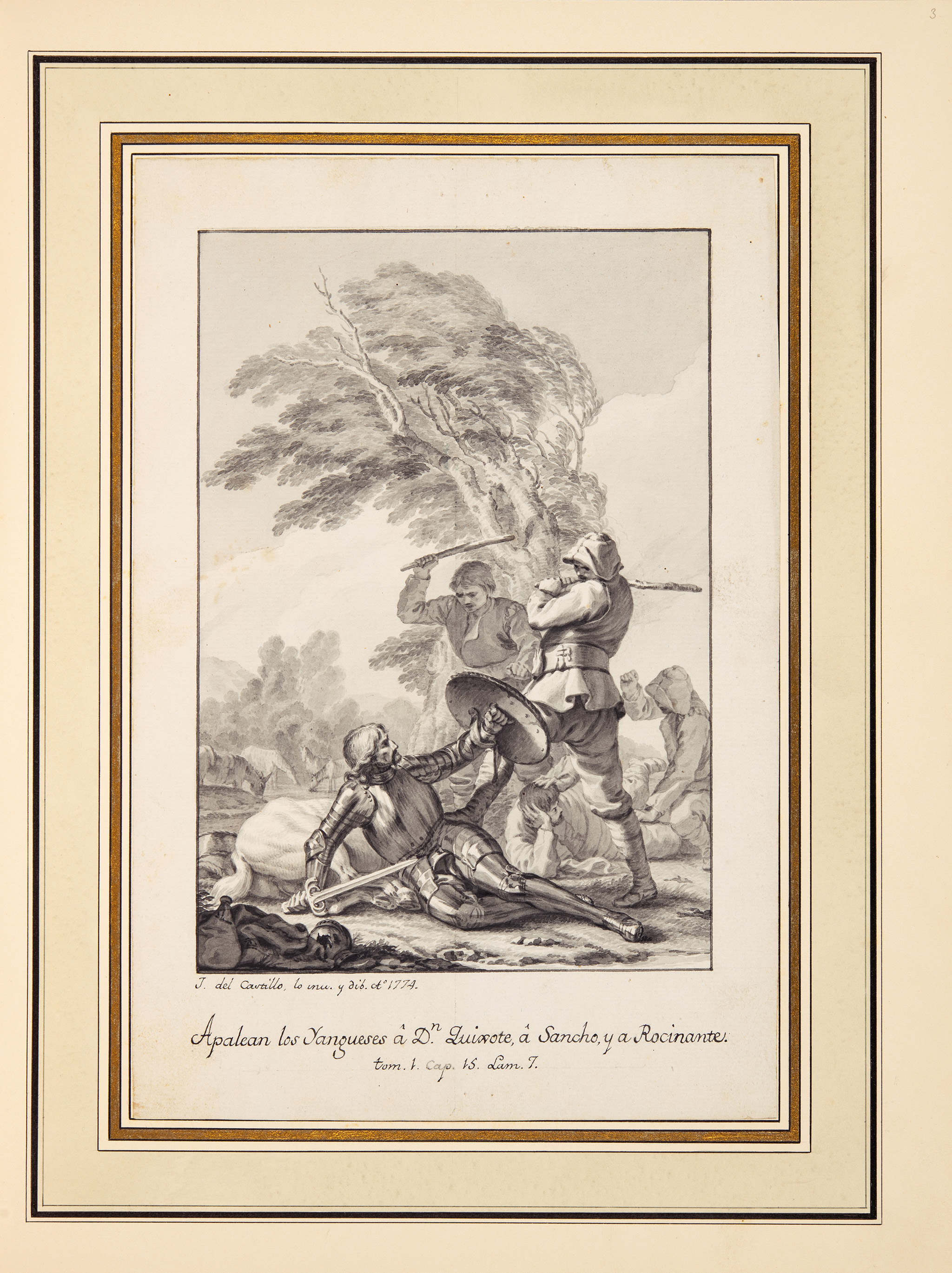

The technical complexity of printmaking entailed a variety of processes of which the starting point was always a drawing – in this case specifically termed a ‘preparatory drawing’. It was sometimes made by the printmaker but was usually commissioned from a draughtsman; that way, the printmaker simply reproduced it faithfully. But before the composition could be engraved or etched, the drawing needed to be transferred to a copper plate. As the design that is incised on the copper plate is reproduced in reverse in the impression on paper, the drawing needed to be laid out facing the opposite direction on the plate. For this purpose, printmakers developed different transfer techniques that preserved the integrity of the drawing, which needed to continue to serve as a model, by making duplicates that we call tracings and counterproofs.

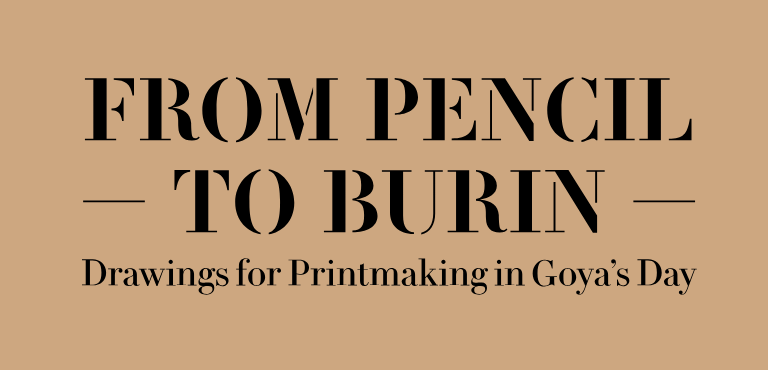

José del Castillo. Don Quixote beaten by the Yangueses, 1774. Preparatory drawing. Brush and bistre ink wash. Barcelona, Biblioteca de Catalunya

The Spanish Royal Academy’s edition of Don Quixote (1780) is the finest example of the process of creating an illustrated book in 18th-century Spain. The Academy took particular care over the choice of the passages to be illustrated and thoroughly supervised the drawings. Numerous designs still survive from this process, both preliminary and final versions. The latter served both as presentation pieces to show the academicians and as models for the printmaker, who needed to transfer them faithfully to the copper plate. There are known tracings of the outlines of the composition specifically made by the printmaker for transfer to the copper plate. Working proofs, impressions taken during the engraving/etching process, enabled the printmaker to ensure that work on the copper plate was progressing satisfactorily. A final proof was made before lettering (addition of the name of the makers of the drawing and the engraving).

Francisco de Goya. Dream. Teacher witch giving lessons to her disciple on the latter’s first flight, 1796-97. Preparatory drawing with platemark. Pen, iron gall ink and black chalk lines. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Drawings could be transferred directly to the plate, as Goya did: he dampened the drawing, placed it on a wax-coated copper plate and ran them both through a press. But it was more common practice to trace the outline of the drawing. It could be traced on fine paper using a glass light box. A counterproof could also be taken by running the drawing through the press together with a blank sheet of paper. Lastly, it could be traced on oiled transparent paper or a sheet of gelatin paper. These drawings were transferred to the plate using another tracing, by rubbing the back – or an intermediate sheet – with powdered chalk and going over the contours with a stylus so that the composition was laid out on the copper. They could also be transferred by pricking holes in the outlines and then pouncing: dusting the back of the sheet with powdered chalk so that dots would be marked on the metal.

Rafael Esteve. Fernando VII and Maria Josefa Amalia, 1819. Left: Tracing on glass paper (jelly). Red chalk. Stylus-incised on back. Right: Print. Etching and engraving. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Area 3

Preparatory drawings for printmaking evidence the use of most available 18th-century drawing materials and techniques. The media could be dry (black and red chalk) or water based (different inks applied with pen and brush). Which ones the draughtsman chose depended on many factors: whether the drawing was going to be engraved or etched by him or by another printmaker, as well as the subject-matter and the technical printmaking procedure to be used. Drawings in chalk or with a fine brush, with a predominance of contours and hatching, were easily adapted to the linear language of engraving. In contrast, pen drawings, heightened with wash, were better suited to the freer strokes of etching and aquatint. The drawings most highly valued by printmakers were those that provided the greatest amount of information about both figures and lights, and were generally executed in pen, brush and wash.

Manuel Salvador Carmona. Saint John and Infant Christ Embracing, 1799. Working proof. Etching. Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Calcografía Nacional

Black chalk had been one of the most common drawing materials since the late 15th century. It was in great demand as it was easily obtained and versatile. The softness, density and sharpness of the drawing strokes depended on its composition – clay and particles of carbon. It should be distinguished from charcoal, which comes from burnt twigs of light woods and was never used for preparatory drawings for printmaking. Drawings were commonly begun by sketching the contours of the composition in chalk, as mistakes could be easily erased. These strokes are often concealed by those executed in other media to finish the drawing. But it was also often employed for the whole drawing, as it made it possible to outline the figures and accurately define the volumes depending on how sharp the point was and the pressure exerted.

Luis Paret y Alcázar. Citizen of Bilbao, ca. 1778. Preliminary drawing. Black and red chalk. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Red chalk was widely used during the 18th century by both professional artists and apprentices, as its softness and porousness made the pencil gentler and easier to handle. Its characteristics led handbooks from the 1600s onwards to recommend its use for preparatory drawings for printmaking, as the design could be transferred very well to the copper plate and good counterproofs could also be taken. In addition, its versatility enabled artists to achieve different results depending on the desired effects: they could dampen it to achieve tonal variations or rub it with a rag or stump to blur and soften the more linear strokes. The Gallicism 'sanguine' has been employed since the second half of the 1900s with the same meaning as red chalk.

Ink, applied with a brush or pen, was one of the most commonly used media in preparatory drawings for printmaking. The variety of available inks and instruments for applying them offered artists a wide range of possibilities to suit the specific needs of each work. The most popular kind were iron gall ink (which is obtained from oak or holm oak galls and undergoes oxidation over time) and bistre (a very stable ink produced from the soot of burnt wood), one of the varieties of which is India ink. As for the instruments, brushes served to apply washes of different intensities. The finest were employed to draw lines with a soft, detailed effect, creating extremely precise drawings. Pens were often used to draw designs that were to be transferred to the plate with a stylus for etching.

Fernando Brambila. Ruins of the Church del Carmen, 1808. Preparatory drawing. Black chalk and grey and pink ink wash. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Area 4

Drawing was an intermediate step in creating prints of an existing model, be it a painting or any other artistic object, nature itself (from landscape to botanical specimens) or the lives of the kingdom's inhabitants – their daily activities or events worthy of being immortalised. It is essential for the draughtsman to copy and capture the model properly, whether in colour or black and white, so that the printmaker can then reinterpret the drawing in an essentially linear language. Fidelity to the original is the key factor in this process, and only if the forms and colours or tones are accurately defined in the drawing will the expert printmaker be able to translate the original into the language of the graphic medium. Other complementary aspects, such as ornamentation and lettering, also had to be correctly defined in the drawing.

Manuel Salvador Carmona. Portrait of Anton Raphael Mengs (Print), 1780. Etching and engraving. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Drawing and engraving played an extremely important role in disseminating images. A good example is the Self-Portrait of Anton Raphael Mengs painted around 1774–76. It became his most widespread and representative likeness as it was used as a model for illustrating the Spanish edition of a compilation of his works (Obras de D. Antonio Rafael Mengs) published in 1780 on the initiative of José Nicolás Azara. Manuel Salvador Carmona, the painter's son-in-law, was commissioned to make the print. He produced two versions that were criticised for not reproducing Mengs’s features and expression in the painting faithfully enough. As evidenced by the pastel copy of the painting made by Ana María Mengs, the painter's daughter and Cremona’s wife, and the extraordinary ink and brush copy submitted by the printmaker Joaquín José Fabregat in support of his appointment as an academician, the criticism of Carmona was not unwarranted. It demonstrates the importance of having a good drawing as a starting point for achieving an excellent print.

Grids were commonly used to copy paintings. Simple to handle and easy to transport, they consisted of a frame divided into equal squares by threads stretched across at regular intervals. The draughtsman placed a grid between himself and the work to be reproduced. He drew the same grid on a larger or smaller scale on the paper used to make the copy. He then had only to draw the contents of each square on the sheet. This was its main advantage, as it enabled the composition to be reduced or enlarged without having to mark lines on the original and damage it. However, the process required the artist to have an advanced mastery of drawing, as it was still an exercise in copying from life. Scientific draughtsmen also needed to be highly skilled at faithfully reproducing specimens from life, even without a grid.

Pasqual Pedro Moles y Blas Ametller. Ostrich Hunt, 1803. Working proof retouched. Etching. Pen, black ink, grey and brown washes and white lead touches. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

One of the ways in which a draughtsman could facilitate the printmaker's task of representing reality was by applying colour with different pigments and shades of wash . However, prints whose preparatory drawings had been made in this way were not always coloured. Even so, in these cases the presence of colour was a decisive interpretative factor for the printmaker, who had to translate the varying colours of the drawing into a black and white intaglio image. Sometimes the draughtsman captured on paper the impressions and study of colour as well as the effects of light and shade by means of different tonal gradations based on grey washes. In the case of chalk drawings, this was achieved by stumping, which allowed him to soften and tone down the pigment to suggest changes in colour.

Francisco de Goya. The Family of Philip IV, 1785-92. Preparatory drawing. Red and black chalk. Madrid, Private collection

The examples shown here, reproductions of Diego Velázquez's Las Meninas, illustrate the problems faced by draughtsmen and printmakers in the second half of the 1700s when it came to transferring intrinsic qualities of painting, such as brushstrokes and colours, to printmaking, a very different medium that is basically linear and devoid of colour. In Francisco de Goya’s case the drawing attests to his ability to copy the painting faithfully, but the print evidences the difficulty he had translating it adequately into an etching. As a result, the etching was not published and the plate was destroyed. In contrast, Antonio Martínez's drawing shows what happens when the design is not of good quality and the printmaker – who worked in Paris and had not seen the original painting – must limit himself to reproducing it. Although the print is technically good, the result is unsatisfactory, especially to our eyes as we are very familiar with the picture.

Director: José Manuel Matilla

Lecture to encourage the public’s self-guided visit of the temporary exhibition, providing the essential keys to better appreciate and understand the works that make up the exhibitions.

Lecture room. Mondays at 11 am and 5 pm

More info

9, 13, 16 and 20 December 2023. 6:30 pm

Sala de conferencias

Actividad gratuita para los visitantes con entrada al Museo

More infoTesting conference hosted by an external entity

Organized by: