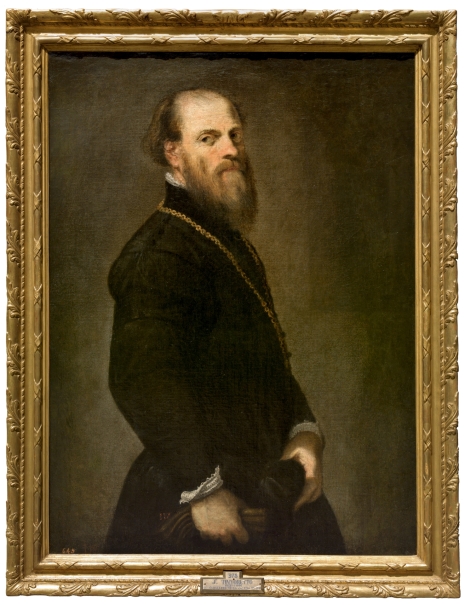

Gentleman with a Gold Chain

Ca. 1555.Room 041

The Nobleman with the Golden Chain is the finest portrait by Jacopo Tintoretto at the Museo del Prado and one of that painter’s most outstanding, overall. While historians disagree about its chronology, the artist’s mastery of both the model’s anatomy and his relation to the surrounding space link it to his so-called portraits in motion from the 1550s. In fact, it is even more sophisticated and efficient than the latter works, as there are no excessive gestures and the twisting body and face are enough to generate a sense of movement that contrasts considerably with the static portraits of the late 1540s.

The absence of exaggerated gestures, a neutral background and strong lighting from the left place this portrait’s expressive weight on the face, which is one of Titoretto’s most powerful. As was customary, it receives particular attention, and while the model is not an old man, his age is marked by his baldness, the deep wrinkles around his eyes and the grey hairs in his beard. Technically, the dense brushstrokes that make up the flesh tones contrast with the lighter, more superficial ones on the hair. The hands are rendered in a surprisingly meticulous fashion that leaves the muscles and veins clearly visible. They may well be the best of any in Titoretto’s portraits. The palette is quite limited, although the artist skillfully exploits the possibilities of the figure’s black clothing by punctuating it with a white collar and cuffs and a gold chain.

Numerous and improbable identities have been ventured for The Nobleman with the Golden Chain, including artists Paolo Veronese or Leone Leoni. The most acceptable was suggested by Pinessi, who considered it a likeness of Venetian aristocrat Nicolò Zen (1515-1565). Whoever he may be, the sitter’s elegant black suit, gloves and gold necklace indicate that he was clearly a distinguished individual.

This work comes from Spain’s Royal Collection and was inventoried at the Galería del Mediodía in Madrid’s Alcázar Palace in 1666. It may be one of the portraits that treatise writer Antonio Palomino mentioned as having been acquired by Velázquez in Venice during the latter’s second trip to Italy. Between 1700 and 1734 its original rectangular format was reduced to an oval, reflecting the new, reigning taste at the Spanish court. That was only a passing trend, however, and by the time it was inventoried at Madrid’s Royal Palace in 1772, it had recovered its original appearance.

El Prado en el Hermitage, Museo Estatal del Hermitage: Museo del Prado, 2011, p.78-79